Existing evidence are not enough to determine whether courts are pro-market or pro-(incumbent)business.

President Obama’s plan to nominate Judge Merrick Garland to the Supreme Court (following the death of Justice Scalia) drew the attention of popular media to a broader issue: are courts and individual justices biased in favor of certain economic policies and interests over others((See examples here, here, here and here.))? The issue of judicial slant normally flies under the radar in popular media, but it has garnered much attention in recent years among legal scholars, economists, and political scientists. Let us take a quick look at the existing body of knowledge, to see whether we can better evaluate the claims in the popular press about a “pro-business” judicial slant.

Many studies of judicial slant do not focus on decisions that touch core economic policies, but rather on issues such as criminal sentencing. Out of the studies that do examine the pro/anti-business axis, an especially notable example comes from Chicago’s William Landes and Richard Posner and Washington University’s Lee Epstein((See Lee Epstein, William M. Landes & Richard A. Posner, How Business Fares in the Supreme Court, 97 Minnesota Law Review 1431 (2013).)). Epstein, Landes and Posner focus on the Supreme Court’s tendencies to side with businesses over time. They show that the Roberts Court tends to be more pro-business than its predecessors.

Another notable example, this time at the state courts level, comes from a series of studies by Emory Law’s Michal Kang and Joanna Shepherd. Kang & Shepherd spotlight the relationships between contributions to judicial election campaigns and judicial decisions. They show an especially pronounced correlation in states where judges run for election on a partisan slate (as opposed to being nominated, or running in a non-partisan elections): contributions from business interests groups to supreme court judges in these states are associated with increased probability that judges will side with these business interests((See Michael Kang & Joanna M. Shepherd, The Partisan Price of Justice: An Empirical Analysis of Campaign Contributions and Judicial Decisions, 86 New York University Law Review 69 (2011). See also Joanna Shepherd, Justice at Risk: An Empirical Analysis of Campaign Contributions and Judicial Decisions, American Constitution Society for Law and Policy (2013).)).

How do these studies define and measure the supposed pro-business slant? To simplify, they do it by counting wins. Whenever a case involves business on one side versus an individual, governmental organization or non-profit on the other side, a win for the business litigant is scored under the pro-business column, and vice versa. Such a method allows for large-n statistical studies. But it also limits what we can truly infer about judicial bias in economic issues. For one, the counting-wins method muddies the distinction between pro-business and pro-market. When judges side with specific business litigants they do not necessarily side with the market. A decision in favor of incumbent interests may, for example, erect barriers to entry and hurt competition. What gets coded as pro-business may, in fact, be pro-big-business (as Epstein, Landes and Posner themselves acknowledge((See Epstein, Landes and Posner (2013), at p. 1435.))).

Another difficulty stems from omissions. A method that counts only the cases in which businesses appear as the primary-named plaintiffs or defendants is bound to miss judicial decisions with big impact on business interests. To illustrate, the famous Citizens United v. FEC. decision greatly affects businesses’ ability to influence politics, yet it is not counted as pro-business (or counted at all) under existing methods, simply because no business entity is the primary plaintiff/defendant((See Joshua Fischman, Do the Justices Vote Like Policy Makers? Evidence from Scaling the Supreme Court with Interest Groups, 44 Journal of Legal Studies S269 (2015).)). Epstein, Landes and Posner show how in more than one fifth of the cases where the Chamber of Commerce submits a brief to court, businesses are not the named plaintiff/defendant((See Epstein, Landes and Posner (2013), at p. 1439.)). As a result, even though these cases likely touch important business issues (why would the Chamber submit a brief otherwise?), some of the existing studies omit them.

Yet another limitation stems from weighting. The counting-wins method puts equal weights on each case. But in reality certain judicial decisions affect all businesses (think narrow interpretation for requirements to certify a lawsuit as class action; or a broad interpretation for upholding mandatory-arbitration clauses), while other decisions’ impact is limited only to the case at hand.

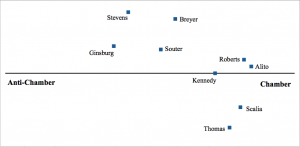

To be sure, it is easier to poke holes in the methodology than to come up with a viable alternative. One alternative method would be to manually code cases, making sure you count all the cases that matter and assign the “proper” weights to cases that matter more. Yet, as one could imagine, such method suffers from too much subjectivity and is limited in its ability to cover a large sample. Another method to identify the court’s position is by comparing it to the position taken by interest groups. Northwestern’s Joshua Fischman, for example, uses the positions that the Chamber of Commerce adopts in briefs submitted to courts to identify a policy dimension, and then tracks how closely judges’ positions align with the Chamber’s((See Fischman (2015))). Yet such “spatial analysis” suffers fro

m its own limitations, including the fact that there are not enough briefs submitted by the Chamber in lower courts and in state courts (as opposed to in the Supreme Court) to identify policy dimensions.

Overall, as is often the case with complex phenomena, a closer look at the evidence of judicial bias calls for treating them with a healthy dose of skepticism.