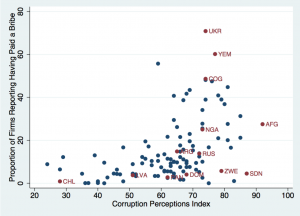

New graph compares corruption perception indexes with reported cases of corruption.

What is the best way to measure corruption, and can there be a reliable way to accurately measure corruption levels? For decades, social scientists have been debating these questions. Due to its illusive nature, and the varying definitions of it, for the past 20 years the most common measures of corruption—such as Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI)—have focused on perceptions of corruption (as determined by experts), instead of experience.

Recent years, however, have seen a number of new tools that aim to measure the experiential side of corruption, such as the World Bank’s Enterprise Surveys, in which firms are asked about their experiences with corruption, whether they paid bribes, and how much (or how often) they had paid.

Is there a correlation between the perception of corruption, and reported cases of it? A new graph, prepared by Mathieu Cloutier from the University of Chicago, compared the rate of firms that reported paying bribes within certain countries with the countries’ score on the Corruption Perception Index. To measure the number of firms that paid bribes, Cloutier relied on World Bank surveys published since 2010, covering 75,000 firms in 122 developing countries.

Interestingly, the graph shows that while there is some correlation between perceptions of corruption and reported cases in countries that are considered less-corrupt (according to their CPI scores), this correlation starts to break down in countries that scored high on the perception index.

One possible reason for this, Cloutier notes, is that the attempt to aggregate the different types of corruption—such as embezzlement, collusion, and bribery—under one catch-all measure might be a losing battler. Ukraine, for instance, has a significant number of firms reporting that they had to bribe public officials, but its CPI score is relatively lower. On the other hand, Sudan has a very high CPI score, and yet not many firms in Sudan reported that they’ve had to pay bribes. Trying to measure corruption as an homogeneous perceived measure, he concludes, might not not a very useful exercise.