President Barack Obama issues an executive order that calls on federal government agencies to promote competition within uncompetitive markets.

President Barack Obama launched a broad new initiative today, issued through an Executive Order, that calls on departments and agencies of the Federal government to take measures to recognize uncompetitive markets and promote competition within them through executive actions.

The announcement, accompanied by a 17-page brief by the White House Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) detailing a decline in competition in numerous sectors within the American economy, ordered the relevant government agencies to report back within 60 days with a list of specific areas where they can promote competition, the steps they can take, and when they intend to do so.

In a statement released today, the White House acknowledged the steep price Americans pay due to anti-competitive behavior: “across our economy, too many consumers are dealing with inferior or overpriced products, too many workers aren’t getting the wage increases they deserve, too many entrepreneurs and small businesses are getting squeezed out unfairly by their bigger competitors, and overall we are not seeing the level of innovative growth we would like to see. And a big piece of why that happens is anti-competitive behavior—companies stacking the deck against their competitors and their workers. We’ve got to fix that, by doing everything we can to make sure that consumers, middle-class and working families, and entrepreneurs are getting a fair deal.”

The first action in Obama’s new initiative is to open the market for set-top cable boxes. The administration has singled out the set-top box market as an example of anti-competitiveness leading to inferior and overpriced products for consumers. Invoking the break-up of AT&T’s monopoly in the 1980s as an example of how competition can lead to an improvement in service and new innovations, the White House statement says: “99 percent of all cable subscribers lease a set-top box to get their cable and satellite programming. It sits in the middle of our living rooms, and most of us don’t think twice about it. But that same study found that the average household pays $231 per year to rent these often clunky boxes. And, while the cost of making these boxes is going down, their price to consumers has been rising. Like the telephones in 1980s, that’s a symptom of a market that is cordoned off from competition. And that’s got to change.”

The administration called on the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to open up the set-top box market for competition, so that subscribers will be able to purchase their own devices to watch cable or satellite programming instead of leasing it from cable companies. Calling the set-top box initiative “the mascot” of its new pro-competition push, the administration noted that Obama’s executive order goes much further than that, aiming to stoke competition throughout the American economy, “so that no corporation can unfairly squeeze their competitors, their workers, or their customers at everyone’s expense.”

The executive order acknowledges that a policy that maintains and supports a fair, efficient, competitive marketplace “is a cornerstone of the American economy. Consumers and workers need both competitive markets and information to make informed choices.” It also notes “competitive markets also help advance national priorities, such as the delivery of affordable health care, energy independence, and improved access to fast and affordable broadband. Competitive markets also promote economic growth, which creates opportunity for American workers and encourages entrepreneurs to start innovative companies that create jobs.”

Anti-competitive measures “such as unlawful collusion, illegal bid rigging, price fixing, and wage setting, as well as anticompetitive exclusionary conduct and mergers stifle competition and erode the foundation of America’s economic vitality,” says the order, that instructs federal agencies to report within 60 days with a detailed list of “recommendations on agency-specific actions that eliminate barriers to competition, promote greater competition, and improve consumer access to information needed to make informed purchasing decisions… as well as timelines for completing those actions.”

The White House announcement was accompanied by a 17-page issue brief, prepared by the CEA, the agency that advises the President on economic policy, on the benefits of competition. The brief acknowledges that the American economy has become less competitive and more concentrated in recent decades, and suggests that robust enforcement of antitrust laws can serve to mitigate this problem.

The CEA lists a number of underlying reasons for the decrease in competition across the American economy, among them “efficiencies associated with scale, increases in merger and acquisition activity, firms’ crowding out existing or potential competitors either deliberately or through innovation, and regulatory barriers to entry such as occupational licensing that have reduced the entry of new firms into a variety of markets.” It also makes the case that consumers and workers would benefit from concerted government action to promote competition “in a variety of industries.”

The CEA relies on a large number of academic studies to argue that competition benefits consumers and workers, and that firms’ abuse of monopoly power may harm workers and consumers alike, by leading to overpricing, lower quality, and lower wages. “The presence of many firms in a market does not ensure competition. Under certain conditions, firms may be able to collude with each other to create and abuse market power, for example by agreeing to raise prices or by restricting output (thereby raising prices) to consumers or by restricting wage growth for workers,” the Council writes, noting that in the United States price-fixing is illegal and that the detection and prosecution of “collusive cartels” is and should be an important priority of antitrust agencies.

America’s concentration problem

The President’s economic advisers didn’t stop at outlining the benefits of competition. The CEA goes on to diagnose one of the major ailments affecting the American economy today: in parts of the economy, at least, competition appears to be declining. The paper connects this decline in competition to three main trends: increasing industry conc

entration, increasing rents accruing to a few firms, and lower levels of firm entry and labor market mobility.

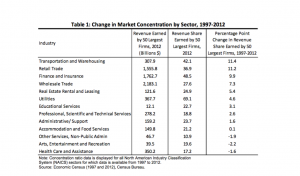

The brief then provides a detailed list of evidence that show increases in concentration and rents. The rise in concentration across American industry can be seen in a table from the U.S. Census Bureau that tracks the share of revenues earned by the 50 largest firms in every industry:

In the majority of industries surveyed by the Census Bureau, the period of 1997-2012 has seen increases in the share of revenue obtained by the 50 largest firms. Other industry-specific studies, the CEA brief notes, have found similar results over longer period of time. Dean Corbae and Pablo D’Erasmo (2013), for instance, found that the share of the ten largest banks in the U.S. in the national loan market increased from about 30 percent in 1980 to about 50 percent in 2010. Their share in the deposit market increased from 20 percent to 50 percent during the same period.

The CEA cautions that this data “is neither a necessary nor sufficient condition to indicate an increase in market power.” Instead, it notes, “antitrust authorities direct their attention to concentration at the relevant market level for each product or service,” but that type of data only exists in a few industries, where increasing market-level concentration can be found. The average Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI)—a commonly accepted measure of market concentration—for hospital markets, for example, increased to a level associated with just three equal-sized competitors per market, according to a 2015 study by Martin Gaynor, Kate Ho, and Robert Town. Similar increases in the average HHI have been documented in the market for wireless providers, and the railroad market.

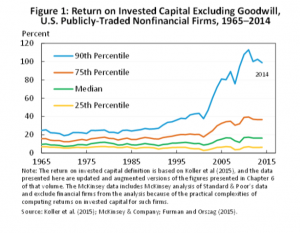

Another troubling trend is that the gap between the most successful firms and the median firm has grown tremendously over the last two decades. The table below, showing the returns on invested capital for public non-financial firms, demonstrates the effect of concentration: firms at the 90th percentile are seeing returns on investments that are “more than five times the median.” Twenty five years ago that figure was closer to two.

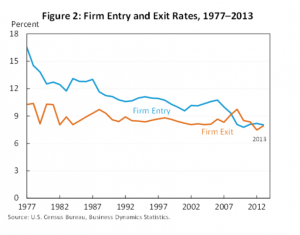

The CEA also spotlights evidence of a decline in labor-market dynamism—the frequency with which workers move from one job to another—and in the number of new firms each year. The Census Bureau’s Business Dynamics Statistics for 1977-2013 indicate that the rate of new firms entering markets have declined over time, whereas the rate at which firms exist markets remained pretty steady.

The links between these factors, the CEA cautions, are not clear. “On the one hand, it could be that a decrease in firm entry is leading to higher levels of concentration, which leads to higher rents. On the other hand, it could be that higher levels of concentration are providing advantages to incumbents which are then used to raise entry barriers, leading to lower entry. Or it might be that some other factor is driving these trends. For example, innovation by a handful of firms in winner-take-all markets could give them a dominant market position in a very profitable market that could be difficult to challenge, discouraging entry.” Nevertheless, it concludes, these trends point out to a decrease in competition that may require attention from policymakers and regulators.

Solution: Tough Enforcement of Antitrust Laws

The CEA focuses on a number of possible reasons for the apparent increase in concentration, including deliberate anti-competitive behavior by corporations, such as “price-fixing, bid-rigging, and market-allocation agreements,” and a rise in M&A activity.

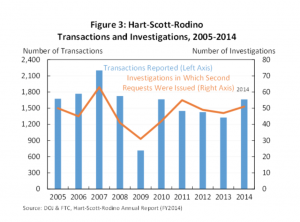

The past few years have seen a sharp increase in the value of reported M&A deals. Global mergers and acquisitions topped $5 trillion in 2015, with $2.5 trillion of this activity located in the U.S. Deals surpassing $10 billion accounted for 37 percent of the global total, almost double the five-year average of 21 percent.

While the value of mergers and acquisitions has spiked in recent years, the number of transactions reported to antitrust authorities has been more or less flat over the past decade. That is partly because while the number of mergers remained relatively stable, each merger on average is much bigger nowadays, involving firms with bigger market shares. The number of investigations launched by antitrust authorities to determine whether a merger is likely to harm competition has been relatively stable as well.

When it comes to anti-competitive behavior by firms, one possible solution is tough enforcement of antitrust laws. The CEA details a number of avenues by which regulators and policymakers can challenge and curb anti-competitive behavior. Also, it observes an increase in enforcement in recent year.

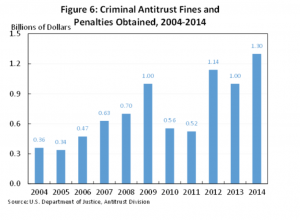

Criminal prosecutions of antitrust violations by the Department of Justice have increased since 2009, according to the paper. Between 2009 and 2014, the number of cases filed by the DOJ against corporations and individuals has risen by more than 60 percent compared with the previous

five years period. During that period, the DOJ charged more than 310 individuals and 110 corporations. Subsequently, there has been a rise in criminal fines: “in 2009-2014, the DOJ obtained more than $5.4 billion in criminal fines and penalties, including a record $1.3 billion in 2014.”

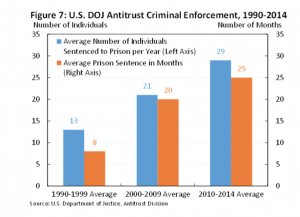

In addition, the CEA details a rise in the number of prison sentences for antitrust violations, and in the length of prison sentences: “Since 2010, the average number of individuals sentenced to prison each year for criminal antitrust violations has increased 38 percent and the average sentence has increased from 20 months in 2000-2009 to 25 months in 2010-2014.” The average number of individuals sentenced to jail has also increased, from 21 in the decade of 2000-2010 to 29 in 2010-2014. “Over time, these enhanced criminal enforcement activities could have a deterrent effect,” CEA members conclude.

The CEA goes on to list a number of ways in which government agencies can engage in “sector-specific regulation and rule-making” in order to promote market competition. Examples include the Department of Transportation’s efforts to divest airlines of certain flight “slots” in favor of new competitors, the FCC’s enforcement of net neutrality that prevented broadband providers from being able to abuse their market power, and the FCC’s actions to allow cell-phone unlocking.

The challenges of digitization

Looking forward, the CEA turns its attention to the digital economy, and suggests regulators should look into “how digitization is impacting competition and whether additional regulation is needed.” In areas possibly in need of enhanced competition, it mentions firms’ increasing use of big data to collect and trade customer information: “Regulators may want to consider whether this ‘big data’ is a critical resource, without which new entrants might have a difficult time marketing to or otherwise attracting customers.”

The CEA also observes that “common ownership of stock by large institutional investors may also lead to anti-competitive effects.” The brief quotes a recent paper by José Azar, Martin C. Schmalz, and Isabel Tecu, that argues that institutional investors who own large shares in the biggest firms within an industry “implicitly encourage the firms they own not to compete with each other, thereby raising profits.”

Further study of the anti-competitive effects of common ownership is warranted given that many U.S. industries are oligopolies and that the role of institutional investors has grown over the last 30 years,” the CEA notes.

“Free markets have the potential to provide great improvements in living standards, channeling resources to productive uses and providing consumers with quality and choices. Sometimes, though, abuses of market power by firms can undermine many of these potential benefits,” the CEA concludes. “Some indicators suggest there is more market concentration, higher profits for a few firms, and declining entry, all of which could result from less competition. Competition policies and robust reaction to market power abuses can be an important way in which the government makes sure the market provides the best outcomes for society with respect to choice, innovation, and price as well as fair labor and business markets.”