The above question — posed by Brucest1, a reader of this blog — is extremely important and deserves a fully articulated answer. Brucest1 seems to conclude that a good CEO ought to be a crony capitalist: “Given the deep and often perverse immersion of our governments in business, how can a CEO in good conscience not be a Crony Capitalist.”

Bruce is in good company. At a recent faculty meeting discussion on the size of fines imposed on companies caught doing false advertising, a colleague described the question of “is false advertising profitable?” as “whether companies ought to use false advertising.” Possibly, it was a slip of tongue, but a slip of tongue indicative of the confusion present even among business school faculty. If fraud pays, should CEOs commit corporate fraud in the pursuit of shareholders’ value? Should they corrupt and deceive as long as it is profitable to do so? Is this a moral obligation, a legal obligation, a business principle, or simply the result of survival instincts in a competitive marketplace?

I leave to people more qualified than me the moral dimension of the question, albeit I doubt that any moral code would make it a more duty to undertake any of these actions.

From an economic principles’ point of view, however, the question is clear. The pursuit of shareholders value maximization produces desirable social outcomes only under certain conditions. One of these conditions is that the law is not violated. In his famous 1970 piece, Milton Friedman clearly states this principle. Most people remember the first part of his statement: “There is one and only one social responsibility of business–to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits.” But the sentence continues “as long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.” Thus, from an economic point of view there is no doubt: a CEO in good conscience does not need to be Crony Capitalist.

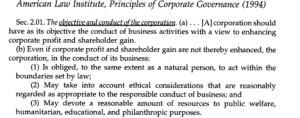

I am not a lawyer, so for the legal perspective I defer to the Principles of Corporate Governance of the American Law Institute (see below).

Thus, even from a legal point of view a CEO in good conscience does not need to be Crony Capitalist.

Is it then just the survival instinct that forces CEOs to become crony capitalist, as seems to suggest also NathanW? Here I will make two points. First, it is not obvious that bribing benefits shareholders. For example in a paper published this month in the Accounting Review, Healy and Serafain show that bribing increases sales, but not profits.

Second, even if bribing improves value, the reasons why a CEO is “forced” to do so might be twofold: the fear of her firm failing in the marketplace and the fear of losing the job. For large – mostly oligopolistic – companies, the former problem is not so serious. The latter could be. If the CEO fears to be replaced, though, this fear does not come from the risk of a hostile takeovers (which after the 1980s have all but disappeared), but only from pressure coming from the Board. If this is the case – and remains to be determined—what we need to fix is the culture in Boardrooms and the way board members are appointed, because if they generate this kind of pressure they are acting wrongly, both from the legal and the economic point of view.

If the point is simply that it is easier to make money, by defrauding, bribing, and cheating, then the question is why. The answer is probably that we need to increase enforcement or penalties or both, because our societal incentives are distorted.

Thus when the crony behavior requires violating the law, there is no doubt that a CEO in good conscience does not need to be Crony Capitalist. The answer is more complex when the crony behavior is perfectly legal – like lobbying , but it still contributes to distorting the rules of the game in a way that is detrimental to society, but very profitable for the lobbying firm. I will dedicate a future post to deal with it.